PDF(4043 KB)

PDF(4043 KB)

PDF(4043 KB)

PDF(4043 KB)

PDF(4043 KB)

PDF(4043 KB)

基于遥感数据量化黄河三角洲刺槐林的边缘效应

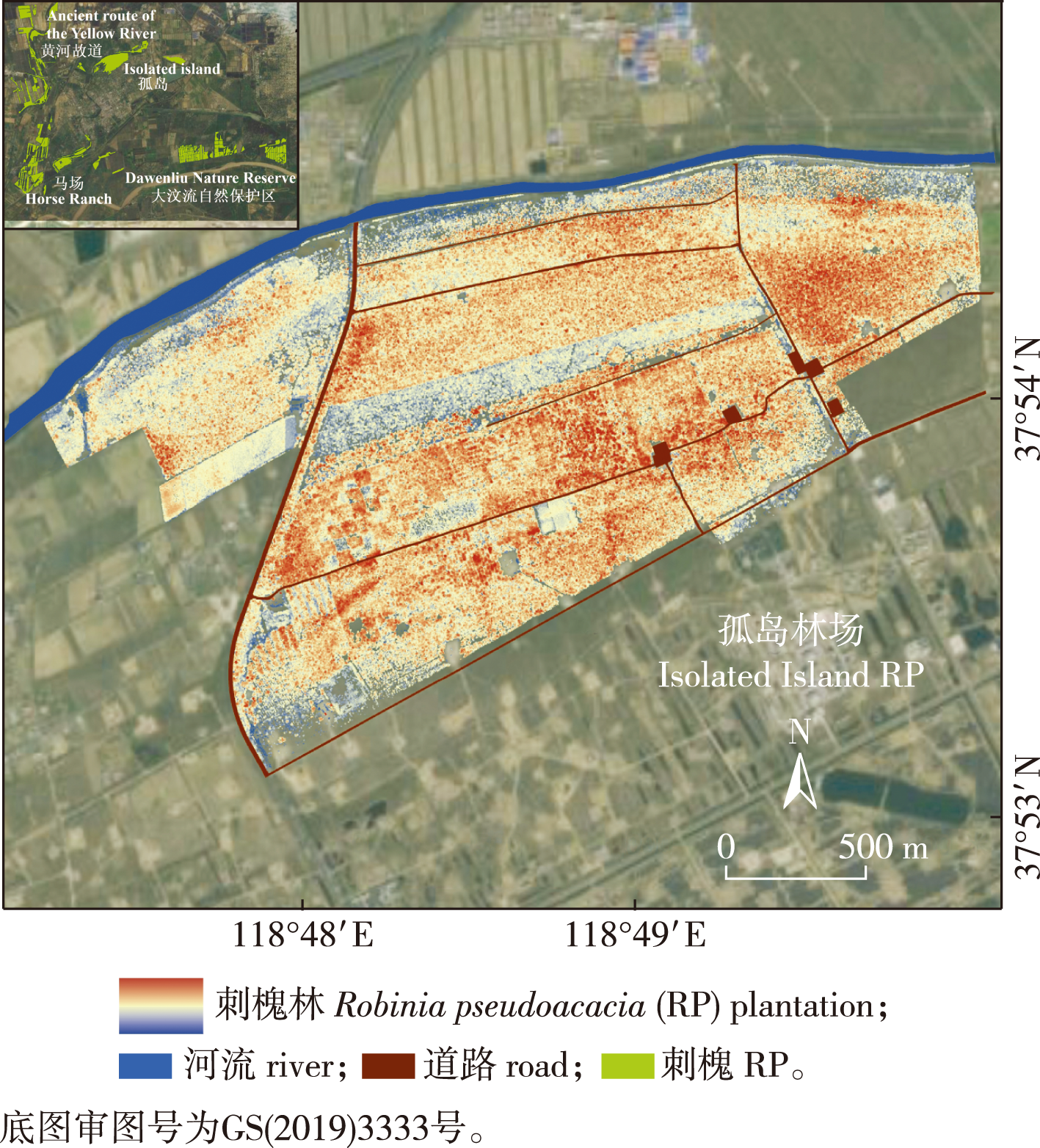

Quantification of the edge effect of Robinia pseudoacacia plantation in the Yellow River delta based on remote sensing data

【目的】边缘效应是指在不同生态系统交界处,由于生态因子的差异及相互作用,引发系统内某些组分显著变化的现象。这一效应广泛存在于森林、湿地、草原等生态系统中。研究森林边缘效应对生态保护、营林管理、气候变化应对和碳储量计算具有重要意义。【方法】以黄河三角洲刺槐人工林为研究对象,利用UAV-LiDAR和Sentinel-2遥感数据,分别提取7个结构指标和3个生理指标,量化分析人工林三维结构和生态功能的边缘效应,并探讨不同边缘类型的边缘效应特点。【结果】①边缘效应对刺槐人工林分结构产生了负面影响。边缘区域的林分树高降低1~5 m、覆盖度减少7%~53%、叶面积指数(LAI)下降10%~77%,林分密度下降6%~52%,同时其冠幅面积和体积也减小。②边缘效应对森林生态功能也产生了负面影响,如削弱了植被的光合作用,其吸收的光合有效辐射(FAPAR)降低8%~50%,叶绿素含量下降9%~72%,冠层含水量也下降8%~50%。③不同边缘类型的影响范围不一样,河流边缘的影响范围可达150 m,而道路边缘影响强度较小,范围约为30 m。【结论】边缘效应对黄河三角洲滨海防护林的植被结构和生态系统功能产生了多维度影响。本研究有助于滨海防护林管理和生态保护,帮助应对气候变化与区域环境退化。

【Objective】The edge effect refers to the phenomenon that some components within the ecosystems change significantly due to the differences and interactions of ecological factors at the junction of different ecosystems. This phenomenon is ubiquitously observed across diverse ecosystems including forests, wetlands and grasslands. The investigation of forest edge effects holds substantial importance for advancing ecological conservation efforts, enhancing forestry management practices, addressing climate change impacts, and refining carbon storage estimations.【Method】This study quantified edge effects in Robinia pseudoacacia plantations in the Yellow River delta using UAV-LiDAR and Sentinel-2 data. Seven structural and three physiological indices were analyzed to assess 3D structural and ecological functional variations, with distinct edge effect patterns identified across different edge types.【Result】(1) The edge effect significantly altered vegetation structural parameters, with observed reductions of 1-5 m in tree height, 7%-53% in vegetation coverage, 10%-77% in leaf area index (LAI), and 6%-52% in tree density. Canopy structural features, including projected area and volume, also exhibited marked decreases. (2) Ecological functions were substantially compromised at forest edges, manifested by impaired photosynthetic capacity with 8%-50% reduction in fraction of absorbed photosynthetically active radiation (FAPAR), 9%-72% decline in chlorophyll content, and 8%-50% decrease in canopy water content. (3) Edge influence zones showed distinct spatial patterns, with river edges demonstrating an extensive impact range of 150 meters, contrasting with the relatively limited 30-meter influence zone of road edges.【Conclusion】The edge effect exerts multidimensional influences on both structural characteristics and ecosystem functionalities of coastal shelterbelts in the Yellow River Delta. This research provides critical insights for enhancing coastal shelterbelt management and conservation strategies, facilitating the optimization of sustainable forest plantation development, and contributing to climate change mitigation and regional environmental restoration efforts.

滨海防护林 / 刺槐人工林 / 边缘效应 / 植被结构 / 生态系统功能 / 黄河三角洲

coastal shelter forest / Robinia pseudoacacia plantation / edge effect / vegetation structure / ecosystem function / Yellow River delta

| [1] |

王伯荪, 彭少麟. 鼎湖山森林群落分析:Ⅹ.边缘效应[J]. 中山大学学报(自然科学版), 1986, 25(4):31-38.

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

\n \n \n Widespread forest loss and fragmentation dramatically increases the proportion of forest areas located close to edges. Although detrimental, the precise extent and mechanisms by which edge proximity impacts remnant forests remain to be ascertained.

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

Forest fragmentation is pervasive throughout the world's forests, impacting growing conditions and carbon (C) dynamics through edge effects that produce gradients in microclimate, biogeochemistry, and stand structure. Despite the majority of global forests being <1 km from an edge, our understanding of forest C dynamics is largely derived from intact forest systems. Edge effects on the C cycle vary by biome in their direction and magnitude, but current forest C accounting methods and ecosystem models generally fail to include edge effects. In the mesic northeastern US, large increases in C stocks and productivity are found near the temperate forest edge, with over 23% of the forest area within 30 m of an edge. Changes in the wind, fire, and moisture regimes near tropical forest edges result in decreases in C stocks and productivity. This review explores differences in C dynamics observed across biomes through a trade‐offs framework that considers edge microenvironmental changes and limiting factors to productivity.

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

Nearly 20% of tropical forests are within 100 m of a nonforest edge, a consequence of rapid deforestation for agriculture. Despite widespread conversion, roughly 1.2 billion ha of tropical forest remain, constituting the largest terrestrial component of the global carbon budget. Effects of deforestation on carbon dynamics in remnant forests, and spatial variation in underlying changes in structure and function at the plant scale, remain highly uncertain. Using airborne imaging spectroscopy and light detection and ranging (LiDAR) data, we mapped and quantified changes in forest structure and foliar characteristics along forest/oil palm boundaries in Malaysian Borneo to understand spatial and temporal variation in the influence of edges on aboveground carbon and associated changes in ecosystem structure and function. We uncovered declines in aboveground carbon averaging 22% along edges that extended over 100 m into the forest. Aboveground carbon losses were correlated with significant reductions in canopy height and leaf mass per area and increased foliar phosphorus, three plant traits related to light capture and growth. Carbon declines amplified with edge age. Our results indicate that carbon losses along forest edges can arise from multiple, distinct effects on canopy structure and function that vary with edge age and environmental conditions, pointing to a need for consideration of differences in ecosystem sensitivity when developing land-use and conservation strategies. Our findings reveal that, although edge effects on ecosystem structure and function vary, forests neighboring agricultural plantations are consistently vulnerable to long-lasting negative effects on fundamental ecosystem characteristics controlling primary productivity and carbon storage.

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

\n We synthesize findings from one of the world's largest and longest‐running experimental investigations, the\n B\n iological\n D\n ynamics of\n F\n orest\n F\n ragments\n P\n roject (\n BDFFP\n ). Spanning an area of\n ∼\n 1000 km\n 2\n in central\n A\n mazonia, the\n BDFFP\n was initially designed to evaluate the effects of fragment area on rainforest biodiversity and ecological processes. However, over its 38‐year history to date the project has far transcended its original mission, and now focuses more broadly on landscape dynamics, forest regeneration, regional‐ and global‐change phenomena, and their potential interactions and implications for\n A\n mazonian forest conservation. The project has yielded a wealth of insights into the ecological and environmental changes in fragmented forests. For instance, many rainforest species are naturally rare and hence are either missing entirely from many fragments or so sparsely represented as to have little chance of long‐term survival. Additionally, edge effects are a prominent driver of fragment dynamics, strongly affecting forest microclimate, tree mortality, carbon storage and a diversity of fauna.\n

|

| [22] |

|

| [23] |

|

| [24] |

|

| [25] |

In forestry, edge zones created by forest degradation and fragmentation are more susceptible to disturbances and extreme weather events. The increase in light regime near the edge can greatly alter forest microclimate and forest structure in the long term. In this context, understanding edge effects and their impact on forest structure could help to identify risks, facilitate forest management decisions or prioritise areas for conservation.\n

|

| [26] |

SILVA JUNIOR C H L,

|

| [27] |

|

| [28] |

|

| [29] |

|

| [30] |

\n\n\nAlthough anthropogenic edges are an important consequence of timber harvesting, edges due to natural disturbances or landscape heterogeneity are also common. Forest edges have been well studied in temperate and tropical forests, but less so in less productive, disturbance‐adapted boreal forests.

|

| [31] |

|

| [32] |

|

| [33] |

|

| [34] |

|

| [35] |

\n While various relationships between productivity and biodiversity are found in forests, the processes underlying these relationships remain unclear and theory struggles to coherently explain them. In this work, we analyse diversity–productivity relationships through an examination of forest structure (described by basal area and tree height heterogeneity). We use a new modelling approach, called ‘forest factory’, which generates various forest stands and calculates their annual productivity (above-ground wood increment). Analysing approximately 300 000 forest stands, we find that mean forest productivity does not increase with species diversity. Instead forest structure emerges as the key variable. Similar patterns can be observed by analysing 5054 forest plots of the German National Forest Inventory. Furthermore, we group the forest stands into nine forest structure classes, in which we find increasing, decreasing, invariant and even bell-shaped relationships between productivity and diversity. In addition, we introduce a new index, called optimal species distribution, which describes the ratio of realized to the maximal possible productivity (by shuffling species identities). The optimal species distribution and forest structure indices explain the obtained productivity values quite well (\n R\n 2\n between 0.7 and 0.95), whereby the influence of these attributes varies within the nine forest structure classes.\n

|

| [36] |

|

| [37] |

Urgent need for conservation and restoration measures to improve landscape connectivity.

|

| [38] |

|

| [39] |

|

| [40] |

宋音, 王红, 路开宇, 等. 基于CCA方法的黄河三角洲不同健康刺槐林的土壤属性研究[J]. 江西农业学报, 2017, 29(10):48-53.

|

| [41] |

|

| [42] |

In Australia, tree planting has been widely promoted to alleviate dryland salinity and one proposed planting configuration is that of strategically placed interception belts. We conducted an experiment to determine the effect of tree position in a belt on transpiration rate. We also assessed how much the effect of tree position can be explained by advection and environmental conditions. Daily transpiration rates were determined by the heat pulse velocity technique for four edge and 12 inner trees in a 7-year-old Tasmanian blue gum (Eucalyptus globulus) plantation in South Australia. Various climatic variables were logged automatically at one edge of the plantation. The relationship between daily sap flow and sapwood area was strongly linear for the edge trees (r2 = 0.97), but only moderately correlated for the inner trees (r2 = 0.46), suggesting an edge effect. For all trees, sap flow normalized to sapwood area (Qs) increased with potential evaporation (PE) initially and then became independent as PE increased further. There was a fairly close correlation between transpiration of the edge and inner trees, implying that water availability was partially responsible for the difference between inner and edge trees. However, the ratio of edge tree to inner tree transpiration differed from unity, indicating differences in canopy conductance, which were estimated by an inverse form of the Penman-Monteith equation. When canopy conductances were less than a critical value, there was a strong linear relationship between Qs of the edge and inner trees. When canopy conductances of the edge trees were greater than the critical value, the slope of the linear relationship was steeper, indicating greater transpiration of the edge trees compared with the inner trees. This was interpreted as evidence for enhancement of transpiration of the edge trees by advection of wind energy.

|

| [43] |

Assessing the persistent impacts of fragmentation on aboveground structure of tropical forests is essential to understanding the consequences of land use change for carbon storage and other ecosystem functions. We investigated the influence of edge distance and fragment size on canopy structure, aboveground woody biomass (AGB), and AGB turnover in the Biological Dynamics of Forest Fragments Project (BDFFP) in central Amazon, Brazil, after 22+ yr of fragment isolation, by combining canopy variables collected with portable canopy profiling lidar and airborne laser scanning surveys with long‐term forest inventories. Forest height decreased by 30% at edges of large fragments (>10 ha) and interiors of small fragments (<3 ha). In larger fragments, canopy height was reduced up to 40 m from edges. Leaf area density profiles differed near edges: the density of understory vegetation was higher and midstory vegetation lower, consistent with canopy reorganization via increased regeneration of pioneers following post‐fragmentation mortality of large trees. However, canopy openness and leaf area index remained similar to control plots throughout fragments, while canopy spatial heterogeneity was generally lower at edges. AGB stocks and fluxes were positively related to canopy height and negatively related to spatial heterogeneity. Other forest structure variables typically used to assess the ecological impacts of fragmentation (basal area, density of individuals, and density of pioneer trees) were also related to lidar‐derived canopy surface variables. Canopy reorganization through the replacement of edge‐sensitive species by disturbance‐tolerant ones may have mitigated the biomass loss effects due to fragmentation observed in the earlier years of BDFFP. Lidar technology offered novel insights and observational scales for analysis of the ecological impacts of fragmentation on forest structure and function, specifically aboveground biomass storage.

|

| [44] |

|

/

| 〈 |

|

〉 |